Meatspace Memes vs. Internet Memes

What do the Peeing Calvin and Darwin Fish stickers teach us?

Do memes require the internet? In a sense, this is an bogus question, since by Dawkin’s (1989) definition of meme it is obviously answered in the negative. Clearly the interesting question is do internet memes require the internet? An internet meme is usually actually an image macro meme (distracted boyfriend or awkward penguin, etc.). The history of the image macro is interesting in itself: as the term “macro” implies, originally these were sequences of commands that facilitated the labeling and posting of images on internet forums or message boards. A lot of the images that were posted on some of these message boards were memes consisting of an image framed by a top and bottom text. Metonymically these memes were them referred to as image macros. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image_macro). Lolcats, advice animals, Scumbag Steve, Success Kid are all image macros. Many Chuck Norris facts are presented as image macros. The “One does not simply walk into Mordor” is another example of a common genre consisting of taking a still from a movie or TV show and framing it with text.

Obviously, again, not all memes that spread on the internet are “internet memes” in the sense of being image macros. The terminology is confusing, so it’s worth recapping: Dawkin’s memes include internet memes (i.e., memes that propagate through the internet). The most salient internet memes are image macros memes but obviously there can be other internet memes that are not image macros (for example, videos, sounds, or alt-text, the popup descriptions that appear if you hover the mouse over an image).

I should introduce a caveat here: most definitions of “internet meme” are in fact definitions of meme cycles. A single meme is an instance of, say, the distracted boyfriend meme. The overall meme “Distracted Boyfriend” is the abstract sum total of all the variants of the “Distracted Boyfriend” meme. This distinction, usually silently adopted, is present in Shifman (2014) and goes back to Saussure’s Langue vs. parole distinction which itself harks back to Durkheim (1895). An internet meme is a “social fact,” in other words. While this point is crucial in understanding the status of memes, it is handily irrelevant in this context, as the point I will be making works across both definitions of simplex memes and meme cycles.

Back to memes. Pornhub, the infamous pornography site, plays a drum introduction in each of their videos. The recognizability and semantic connotation of this drumming sequence can be appreciated from a9 seconds video clip which was widely circulated on the internet in which a student plays the very short “sting” (as these percussion phrases are called) at a school assembly and the audience bursts into laughter and general commotion. The inappropriateness of an introductory drum sting associated with pornography at a school assembly introduces an obvious incongruity, which the students pick up on immediately (recall that the whole clip lasts all of nine seconds). Incidentally, the student was apparently suspended, for this stunt. This musical sting (phrase) is a meme, but it is not an “internet meme” (despite spreading on the internet). What makes it a non-internet meme?

We need a better definition setting apart internet memes from memes that happen to be on the internet. According to Wiggins (2019, p. 13) “internet memes require remix but are also heavily dependent on (…) parody and intertextuality [they] (…) are digital, and no known non-digital or non-online example exists” with the proviso that “commodified” versions of the meme do not affect the thesis. This is fair: if one puts a woman yelling at a cat on two pillows, or on a mug, that is obviously a non-digital version of the meme, but it does not affect the original “digital” status of the meme. There are other exceptions as well, which Wiggins lists, but they need not detain us here as they are irrelevant to the present discussion.1 So, by Wiggins’s definition, the Pornhub sting is not an internet meme because it is not remixed and/or parodic. So far so good. But let’s go a little deeper.

In order to test Wiggins’s definition, I will examine two memes that fit the image macro meme definition (the quintessential internet meme) and that however do not originate or even exist significantly on the internet: the peeing Calvin and the Darwin fish. I will argue that these are memes, in the internet-meme sense, that live in meatspace (the real, non-digital world, in which people drink real coffee, buy actual dinners, and go to actual physical places). In other words, I will show that internet memes pre-exist the internet. To put it differently, none of the definitional features attributed to internet memes are unique to memes that appear on the internet. Just to be clear, I quoted Wiggins (2019) as an example, not because he is unique in this definition. The same definition can be found in Wikipedia (“Characteristics of memes include their susceptibility to parody, their use of intertextuality, their propagation in a viral pattern, and their evolution over time.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_meme

The Darwin Fish

The use of a fish to symbolize Jesus and hence Christians goes back to solidly pre-internet era, namely the 1st century AD. The basic ideas was that the Greek word for fish (ἰχθύς) is an acronym for Jesus Christ Son of God and Savior (it works in Greek, see Edmonson, 2010) and Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichthys). This was also accompanied by the symbol of a fish, created by two intersecting curving lines that suggest the shape of a fish (see figure 1).

The use of the fish symbol is documented as far back as Roman times but fades in the 4th century AD (Edmonson, 2010). It resurfaces in the 1980s and is used up to present times. Figure 2 shows a straight up use of the symbolism.

According to Beine & Little (2009) and Edmonson (2010) the first parodies of the fish which included the word “Darwin” and two little legs under the fish appeared in the early 1980s. Combined these two clues evoke the script for EVOLUTION. (Figure 3)

Obviously, the Darwin Fish is a parody of the original Christian fish, which is the founder meme (Shifman, 2014) or as I like to call them, anchor meme. From here a largish number of variants of the parody were produced. One of the earliest was a “Truth Fish” eating the Darwin Fish, obviously a comeback from the religious . Beine and Little (2009) document quite a few: a Buddhist version, an Hindu variant (where the fish has sprouted cow-like udders), a pagan version, and a Jewish version, which doubles up on the joke in that rather than having the word “Pagan” or “Buddha” in the fish-symbol, it has the word “Gefilte” the Yiddish term for “stuffed” in the fish-symbol. Gefilte fish is a popular Jewish dish consisting of ground fish and other ingredients. The RELIGION vs. FOOD script opposition is very frequent in humor. In another variant, the word “n’chips” appears in the fish-symbol. Here we find again the RELIGION vs. FOOD script opposition, but this time instantiated through the “fish and chips” British dish. The DarwinUK site documents several other variants including an “evolve” and T-Rex one (in which a T-Rex is eating a Jesus fish); the T-Rex variant is also documented in Nussbaum (2005). Edmonson (2010) cites a “Satan” and a “Sinner” variants, as well as a “Sushi” variant, a “Robot” variant and a “Flying Saucer” variant. The Wikipedia entry documents a version in which the Jesus fish and the Darwin fish kiss. Nussbaum (2005) is also interesting because it discusses the size of the sales of these stickers. For example, the T-Rex version was a bestseller in 2005. Gibson (2000) also documents numerous other variants, including a “vampire” fish (yes, with teeth) and a “Prozac” variant. Goettlich (2015 p. 109) documents several examples. He argues that, following Baudrillard’s notion of “hyperreality” that the “fish” stickers are no longer parodic (i.e., with a clear target) but pastiches in which “endlessly circulated and endlessly attenuated referential bits” are repeated pointlessly. While there is some degree of plausibility in the idea of recirculation and attenuation (see the discussion of memetic drift in Attardo, 2023), the idea that the Darwin fish, the Pastafarian fish, or the Truth fish are not parodic (and meaningful) seems off the mark. I will return to Goettlich’s outstanding work in other notes.

Cicada (2007) reproduces a sort of evolutionary tree of some of the “fishes” (Figure 4)

The Babylon Bee, always alert to religious themes, wryly commented in 2016 on the issue mocking the pretensions of those who affix these stickers, by grotesquely exaggerating the impact seen a sticker would have on someone. The title of the article is pretty self-explanatory: “Atheist Driver Spots Jesus Fish Eating Darwin Fish, Repents.”

Summing up, in the “Fish meme cycle” we see all the features that we commonly associate with memetic productivity online: remixing, intertextuality, parody, exploitation of the affordances of the medium (e.g., the oval shape of the fish becomes a flying saucer), and meta-stance in which the meme is commented on as meme. However, Knowyourmeme lacks an entry on this meme cycle.

A final consideration on the Darwin meme. This is an example of a “counter-meme” i.e., a meme developed for the purpose of attacking a previous meme. The truth fish eating the Darwin fish is a counter-counter-meme (Godwin, 1994).

Peeing Calvin

Calvin and Hobbes, drawn by Bill Watterson, is beloved cartoon series that ran from 1985 to 1995 and is still being reprinted and widely share don the internet. It is a very wholesome cartoon, partly due to the fact that it appeared originally in newspapers, and hence in a very conservative environment, but also due to the main character being a child, much like Schulz’ Peanuts. Watterson also famously eschewed practically all forms of merchandising of his characters. It is thus rather surprising to have seen a fairly widespread set of images of Calvin urinating on various targets. This is known as “peeing Calvin.” Peeing Calvin is a real-world image meme that exists as decals that auto owners put on their car windows (usually the back).

This is not the only time that a cartoon has been “repurposed” by other artists. Underground comics artists in the 1970s famously parodied Disney’s Mickey Mouse (Levin, 2003). Andrea Pazienza, an Italian comic artist has an entire book of stories titled “Why Goofy looks like a pothead” (1983). Pepe the frog, Matt Furie’s cartoon character, was famously taken over from the alt-right, much to Furie’s chagrin. Of course, the ancestors of all “détournements” are the Tijuana bibles. Snow White seems to have been a favorite target, but Mickey and Minnie are not spared. Examples can be found online (https://bookriot.com/a-history-of-tijuana-bibles/).

So this is not a new phenomenon, in the sense that the repurposing of cartoon characters for satire, countercultural statements, and pornography are common. What is different in the case of the “peeing Calvin” images is that they are very publicly displayed, in fact on one’s car, truck, or other vehicle. In this sense they are very close to the “fish” bumper stickers we discussed above.

Edwards (2014) and Piccoli (2015) provide a thorough description of the peeing Calvin phenomenon, with numerous examples. In a nutshell, the image originates in the mid-1990s in Florida, in which some fan of University of Florida created a sign of Calvin urinating on the letters FSU (Florida State University). In other words, they were part of the UF/FSU rivalry. From there the image spread to the NASCAR environment in which stickers showed Calvin relieving himself on various numbers, matching drivers.

For example, I was able to locate on Ebay a metal license place showing Calvin urinating on a number 3, which apparently is Dale Earnhardt. The seller describes it as “vintage.” The plate will set you back $14.99, in case you are interested.

From NASCAR drivers, Calvin moved on to car makes (Ford, Chevy etc.) and eventually to politicians, presidential candidates, and quite a lot more. However, from what is available on the internet, Calvin’s micturitions show a right-wing slant (not in the sense of the direction of the jet, I mean politically). We find a lot of Obama, Biden/Harris, liberals, etc. but not a corresponding number of Trump/Pence, Bush, etc. Some variants introduce a raised middle finger, presumably to drive home the attitude even more, a “squatting girl” variant (we wouldn’t want to be accused of sexism, would we?), a cowboy hat on Calvin, a Mexican sombrero on Calvin who is peeing on “la migra” (i.e., immigration police; see figure 6),

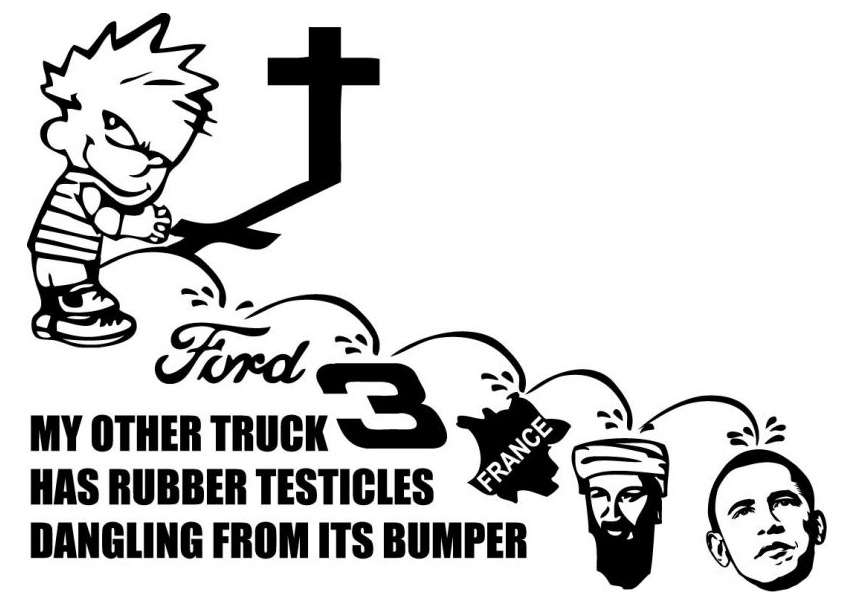

Calvin praying to a cross (minus the urination) and a surreal version in which Calvin is tinkling on an upside down image of Calvin peeing. In another example, Calvin directs the waterworks in a toilet, achieving meta status. Perhaps the ultimate example of memetic drift is the illustration in Weinstein (2014), who unfortunately does not provide a source, which is reproduced in Figure 7 below.

In the example in Figure 7, we can observe almost literally memetic drift. The urinary “bounce” takes us down the history of memetic drift, sans the Florida leg of the trip: Ford, Dale Earnhardt, France (identified by name because the hexagonal shape would have been unrecognizable for the intended audience), Bin Laden, and, in a jarring juxtaposition, Obama, the guy who captured and killed Bin Laden. Of course the author of this image is just throwing together pell mell signifiers (images, in this case), without any care for logic, coherence, or historical fact. The only signified (meaning, connotation) is that the targets of the bounce are disapproved of, for whatever reason. Notice also that since Calvin is urinating on the shadow of the cross, possibly because of the freehand operation needed to join his hands in prayer at the same time, one may suspect a rather surprising high-brow reference to Andre Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987). However, I think a simpler explanation is that the carelessness in assembling the meme explains away the unexpected sacrilegious golden shower: no reference to Serrano, just bad photoshop. Finally, the line about the rubber testicles needs some explanation for non-US readers: the intense insecurity of some American males leads someone who is driving about 7000 pounds of metal (roughly 3 tons, for the metrically inclined) to feel the need to further reassure themselves of their maleness by affixing rubber or metal testicles to the back of their trucks.

Rampton (2022) discusses Watterson’s stance in relation to these stickers. His attitude apparently has evolved for open condemnation (“Only thieves and vandals have made money from Calvin and Hobbes merchandise.”) and attempts to suppress the bootlegged merchandise to a more philosophical stance, in which Patterson ironically muses that the stickers may be his most permanent legacy: "long after the strip is forgotten, those decals are my ticket to immortality."

As we saw, the “Darwin fish” and the “truth fish eating the Darwin fish” are counter-memes. However, the peeing Calvin is not a counter-meme. It is obviously aggressive, that is the whole point of the “pissing on X” trope. However it is aggressive against realia, entities in the world, not other memes. This is not the place to discuss counter-memes in detail. I will do so in another note.

Wrapping up our discussion, these images display parodic and intertextual references, memetic drift, and widespread diffusion (virality). However, no sign of the internet. Knowyourmeme has several entries on Calvin and Hobbes, but not one on “peeing Calvin.” There is no entry for Darwin fish, either, as we saw. In short, these are internet memes, but they are not on/of the internet. QED.

References

Attardo, S. (2023). Humor 2.0: How the Internet Changed Humor. Anthem Press.

Babylon Bee (2016) https://babylonbee.com/news/atheist-driver-spots-jesus-fish-eating-darwin-fish-repents

Beine, D., & Pittle, K. (2009). Hooked on The Fish: The Christian Sign of The Fish (and Co-Option Thereof) as Symbolic Capital. SIL Electronic Working Papers.

Cicada (2007). Can the Darwin fish be improved upon? http://bioephemera.com/2007/04/06/can-the-darwin-fish-be-improved-upon/

Darwin UK. (N.D.) Darwin Fish History. https://www.darwinuk.com/darwin-fish-history.html

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press.

Durkheim, E. (1895) Les règles de la méthode sociologique. Alcan.

Edmondson, T. (2010). The Jesus Fish: Evolution of a Cultural Icon. Studies in Popular Culture, 32(2), 57-66.

Edwards, P. (2014) The tasteless history of the peeing Calvin decal. TriviaHappy. https://triviahappy.com/articles/the-tasteless-history-of-the-peeing-calvin-decal

Gibson, S. (2000). FRESH FISH. Skeptic [Altadena, CA], 8(3), 7.

Godwin, M. (1994). Meme, counter-meme. Wired. https://www.wired.com/1994/10/godwin-if-2/

Goettlich, W. (2015). Interstate interstitials: Bumper stickers, driver-cars and the spaces of social encounter on contemporary American superhighways (Masters’ thesis, Concordia University).

Levin, B. (2003). The Pirates and the Mouse: Disney's War Against the Underground. Fantagraphics Books.

Nussbaum, P. (2005) Bumper Fish Are Latest Symbol in Long Evolution Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2005/10/22/bumper-fish-are-latest-symbol-in-long-evolution/78424268-dbc9-4763-8300-56cd9a682e24/

Piccoli, A. (2015). https://www.mediamatic.net/en/page/233641/the-curious-case-of-peeing-calvin-decals

Rampton, M. (2022). HOW DID CALVIN FROM ‘CALVIN AND HOBBES’ END UP PEEING ON EVERYTHING? https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/calvin-peeing-sticker

Shifman, L. (2014a). Memes in digital culture. MIT press.

Weinstein, A. (2014) Five Fascinating Facts About the History of Peeing Calvin Decals. Gawker. https://www.gawker.com/five-fascinating-facts-about-the-history-of-peeing-calv-1599299196

Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality. Routledge.

Image sources:

Fish symbol

By Fibonacci - Drawn by Fibonacci, modifying Lupin's PD source code a bit., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=533799

ICHTHUS fish symbol on a Mercedes

Oliver Volters Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ichthys_C-Class.jpg

Darwin Fish

Al Seckel, John Edwards Public domain, Wikipedia.

Wiggins (2019, p. 13) is very clear that “For internet memes, remix is an overarching structural requirement absent of any real semiotic information beyond the basic understanding that a core idea or notion is maintained thematically but may not be maintained in similar visual ways.” What this seems to mean is that for Wiggins, remixing is essential in defining internet memes and that the remix itself does not carry any meaning beyond that there is some similarity between the two items being mixed.